Diversified agroforestry systems of cacao: a proof of concept as an alternative to the existing economy for small producers.

Nisao Ogata, Centro de Investigaciones Tropicales (CITRO), Universidad Veracruzana. email:nogata@uv.mx

Jesus Rodríguez Miranda. Departamento de Química, Instituto Tecnológico de Tuxtepec, Oaxaca.

Edgar García Rico. Instituto de Alta Repostería de Xalapa, Xalapa, Veracruz, México. email: cheferico@hotmail.com

Carmen Broca Martínez. Domicilio Conocido, Comunidad Santo Tomás, Cunduacan, Tabasco, Mexico

Summary

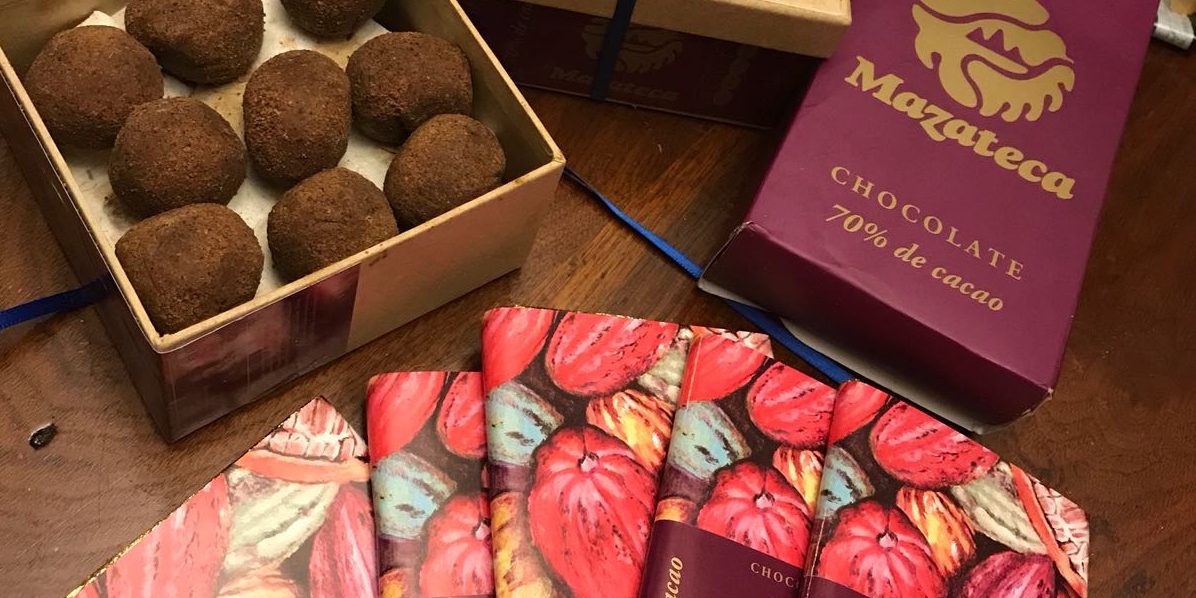

This paper describes the design and development of a proof of concept to fully implement the chain from cacao production on the plantation to the manufacture of high quality chocolate. The work initiated in a context of traditional shade agroforestry diversified systems of cacao as a means of conservation biology practices. A specific variety was chosen for harvesting, fermenting, drying and roasting under specific conditions. In the laboratory, cacao liquor was obtained and transformed into several types of chocolate following European methods and techniques of manufacture and nutrition facts analyses were performed. A brand image, packaging and a store online were designed with the intention of reaching an informed consumer market willing to pay for a high quality chocolate, manufactured under the basis of traditional agroforestry diversified systems of cacao plantations, sustainable use and management of nature and direct economic benefits for small producers.

keywords: cacao, diversification, sustainability, chocolate, development

Introduction

Mexico is considered the second highest biocultural country in the world based on the number of biological species, centers of domestication, agrodiversified systems and indigenous languages spoken (Toledo and Barrera 2008). This biocultural diversity is mainly concentrated in the Southeast where most important reserves of crude oil and water also are found. Paradoxically, in spite of this richness, southern Mexico is the area with the less development in the country not only in economy, but in education, health, nutrition and so…(INEGI 2018). This is the region where rich states such as Oaxaca, Veracruz, Chiapas, Tabasco and Campeche show negative numbers of economic growth (INEGI 2018).

Southern Mexico is where several important commodities are produced (sugar cane, coffee, cacao) but barely processed in the region, so that benefits do not have an impact on the economy and development for the majority of producers, specially those with less than two hectares of land.

The increasing subordination to the global market is leading to dramatic transformations in the region in regard to traditional systems of agriculture, health, migration, loss of cultural patterns and destruction of ecosystems on which at the end we all depend. This situation has also led to small producers, groups, communities, not only in Mexico, to search for new ways to strengthen their societies and explore possibilities to be self-sufficient and autonomous. It also involves a reflection and redefinitions of their identities, comparisons and applications of traditional knowledge and scientific approaches to solve local problems, a present day understanding of their cultural heritage and the way they have coped in the past with the numerous forms of injustice and exploitation (Barkin and Lemus 2015; Boff, 2013).

The production of cacao is not exempt in excluding small producers from the benefits of the global market which leads to transformation of their traditional ways of cultivation and deterioration of culture and ecosystems. The transformation of their traditional ways of cultivation includes traditional diversified agroforestry systems of cacao, designed at least since three thousand years ago as the closest resemblance to a natural tropical rain forest (Ogata 2003; Ogata 2017). The assemblage of these so called “artificial tropical rain forests” is one of the best examples to show a non-occidental approach to domestication where the species of interest is important as far as it is considered in the context of an ecosystem’s species composition. Human beings conduct and orchestrate these artificial tropical forests by considering the canopy trees as the most important functional group of the agroforestry system. Without upper canopy trees there are no leaves, and without leaves there is no organic matter to be transformed by a myriad of organisms to sustain the rest of biological diversity (fungi, plants, mammals, amphibians, reptiles…and of course human beings). Shade diversified agroforestry systems of cacao prevent soil erosion, regulate temperature, precipitation and water availability, especially in controlling the timing by which water is distributed within the forest, to maintain the precise humidity for shade species like cacao (Ogata, 2017). However, nowadays, in the attempt of supplying the global market, traditional cacao plantations are gradually transformed into sun semi-sun exposed monocultures, with the consequent loss of biological and cultural diversity as it is evident in several countries in Africa and Latin America (Ogata 2017; Higonnet and Hurowitz 2017; Ruf 2012, Waldron et al. 2012). In the context of this trend, the bigger the market to be supplied, the more tropical rain forest areas are deforested for cacao plantations as they are turned into sun exposed monocultures to fill demand, to the detriment of the living conditions of small producers and the ecology of such areas.

This paper presents the design and development of a Proof of Concept in the search for alternatives to the existing economy (sensu Esteva 2014) for small cacao producers. The objective consists of developing a different approach to link small cacao production through to the production of high quality chocolate. This includes reaching an informed consumers market willing to pay for a product manufactured under a conservation biology system, where beneficiaries will be small cacao producers. In this way, it is our purpose to set up grounds for people to generate an economic surplus to be managed collectively, reward members who have made important contributions in producing it and share the rest for collective purposes.

The chain: from the plantation to the chocolate bar

The transformation of cacao seeds into chocolate bars and its derivatives is a chain made of a series of links apparently designed as to be isolated from each other in such a way that only the few at the end of the production chain are able to complete the end product and receive the main economic profits. In general, producers of cacao don’t know where the seeds go nor what it becomes. Small to medium manufacturers of chocolate hardly know where the seeds come from, and most consumers don’t know either nor do they know how seeds are transformed to chocolate, or even the real taste of chocolate. The latter is attributed to the influence of the chocolate industry which is responsible for the wide spread idea that chocolate is synonymous with candy, which means that the real taste of chocolate is generally masked with high sugar contents, crushed seeds, marmalades, bread, fructose, etc., with the only purpose of earning more profits out of the chocolate flavor.

The dissociation among the links in the cacao-chocolate production process is evident when comparing the economic situation between the producers of the raw material, that is cacao beans, and the industry of chocolate. The chocolate plant (Theobroma cacao L., Malvaceae) is a small shade tree growing in the rainforests between the tropics of Cancer and Capricorn, where some 10 million hectares are cultivated around the world by about 5.5 million farmers. It is mainly cultivated in Africa and the Pacific Rim (Arvelo et al. 2016). Latin America and the Caribbean devote around 1,750,000 hectares to cacao cultivation where some 350,000 families, that is about 1.5 million people depend on this crop. According with the same source, around 90% of the cacao production in the world rests on small producers (with less than 2 hectares), most of them living in poverty. A painful irony pops up when, in the meantime the small cacao producers and their families struggle every day to survive, the chocolate industry generates around 120,000 million dollars a year! (Arvelo et al. 2016).

To improve the living conditions of small cacao producers is a difficult challenge mainly because the purpose of the cacao production in the world is meant to supply the chocolate industry not to benefit small cacao producers. In general terms, the transformation of cacao into chocolate for industrial purposes does not require special characteristics to prepare the basics of the chocolate that will be transformed into different products such as covers, syrups, etc. As said before this is because the chocolate taste is usually masked with several sugar additives, flour, etc. A mass-market chocolate bar usually contains around 11.4% of cocoa solids, 3% vegetable fat, 20% milk solids, the rest is sugar and a small amount of lecithin as a stabilizer (Cody 1995).

The cacao production

In the first link of the cacao chain of production, small producers are induced to sell the seeds fresh receiving a meager income that becomes just enough for survival. This situation gets worse when governmental programs, industry and even research institutions, encourage small cacao producers to increase the cacao production by transforming traditional shade diversified agroforestry systems into sun, semi-sun exposed cacao monocultures. The consequence of these types of plantations is ecological damages such as an increase in temperature in and around the small producers households, loss of biodiversity corridors (traditional shade cacao plantations are used by wildlife to interconnect among spots of natural vegetation), loss of useful tree species in the upper canopy, shrubs, and a loss of biodiversity in general (Ogata, 2017). The consequences of semi-full sun exposed cacao plantations have been fully documented in Africa, where even protected natural areas are invaded to increase the areas of cacao production, clearing thousands of square kilometers of natural forests with loss of habitat, in particular for endangered species (Ruf 2012; Higonnet and Hurowitz 2017).

In the case of Mexico, there is a deficit for the internal demand of the industry. In 2016, more than 60,000 tons of grains were imported and the internal production reached only around 26,863 tons, that is 41.23% for internal supply (Sagarpa, 2017). As well as in other parts of the world, in general, small Mexican producers have no other option than selling their cacao seeds in fresh to small holders, that is, the next link of the cacao chain. Small holders either ferment or just wash and dry the seeds, pack into sacks and sell to the next link, that is a bigger holder to prepare big shipments for the industry. This season (2018) small producers received in Tabasco State between $0.55 – $0.65 U. S. Dls. per kilogram of seeds in fresh. Small holders, in turn, received between $2.00 – $3.00 U. S. Dls. per kilogram of dried beans. Sometimes, some of them have the opportunity to make deals for special shipments that request specific fermentation and dry conditions. In this circumstances they may receive from $4.00 to 5.00 Dls. per kilogram of dried beans, but this situation is not common. From here, the next links in the chocolate chain may take several routes, for example, chocolate covertures used by chefs in small-medium business like bakery shops and restaurants. A Mexican brand of chocolate coverture commonly used call “semi-bitter” chocolate, is basically a blend of cacao and sugar (with no specification of the amount of cacao content). In a 500,000 person city like Xalapa, in Veracruz State, Mexico, such a product costs around $7.5 U. S. Dls. per kilogram. Another presentation branded as “Bitter” (a little more cacao content, no specified) reaches $9.5-$10.00 U. S. Dls. per Kg. An imported brand of “semi-bitter” in the same city costs around $18.00 U. S. Dls. per Kg. A chocolate bar (80 grams) made by small-medium manufacturers, costs $4-6 U. S. Dls., in supermarkets, airports and chocolates shops. An exclusive chocolate shop in Santa Fe, Mexico City, offers an assorted of 144 pieces of chocolate (around 13 grams each) filled with different types of “ganaches” (meaning fillings made of sugar in different forms such as marmalades, milk, liquor, cocoa butter, etc.) for $128.00 U. S. Dls. The big industry route of cacao leads to different types of “candies”, cakes, chocolate gifts, etc., from where this researche did not have access to detailed costs per item, except to say that it must be a very profitable business.

The cacao production in Mexico

Nowadays, traditional shade diversified agroforestry systems of cacao are disappearing in Mexico. According with agricultural national plan 2017-2030 for cacao (Sagarpa 2017), from 2003-2016 the Mexican cacao production declined in 46.24% (26.23% in yield).

Although in 2016, the Mexican government reported 59,842 hectares of cacao planted, the reality seems to be different. As an example, the region Cunduacan-Comalcalco, a traditional area of cacao plantations in Tabasco State (the highest cacao producer in Mexico), people are changing the land use at a high pace mainly into sugar cane and cattle (Map 1).

The cacao plantations remaining in the region are around forty years old, barely attended, the workforce is mostly elders around 63 years old. The young people are not interested in producing cacao, as soon as they can, they leave to the cities searching for better ways of living (Sagarpa 2015).

Diversified agroforestry systems of cacao

From 2012-2016, we developed a conservation biology and development initiative for small producers in Oaxaca State, in an area not dedicated to cacao plantations and with no previous experience in diversified agroforestry systems. The project was established to transform deforested areas such as grasslands and abandoned coffee plantations into diversified agroforestry systems of cacao. The idea was to introduce this approach as an alternative to the existing economy, by using principles of organization and work such as those proposed by Barkin and Lemus (2015): autonomy, self-sufficiency, solidarity, productive diversification and regional sustainability. After four years, we demonstrated in this area of Oaxaca that diversified agroforestry systems are a reliable alternative for conservation biology, restoration of ecosystems and an alternative to economy for small producers in deforested areas and lowland abandoned coffee plantations (http://etnoecologia.uv.mx/diversidad_biocultural/mazateca/). With this work as a previous experience, in 2017 the present project in Santo Tomás, Cunduacan, Tabasco, Mexico was initiated.

Methods

The project started with a group of 13 people in Santo Tomás, a small community of Cunduacan, one of the three more important municipalities of traditional cacao plantations in Tabasco State, Mexico. The study area is a two hectares of traditional shade diversified agroforestry system of cacao, more than forty years old. This plantation is part of an approximately 20 hectares of contiguous cacao plantations shared with other owners. The diversified agroforestry system upper canopy composition in this area is made by more than twenty species of shade trees and shrubs besides cacao. The main species are: Swietenia macrophylla King, Cedrela odorata L., Tabebuia rosea(Bertol.) Bertero ex A. D.C., Annona muricata L., A. reticulada L., A. glabra L., Gliricidia sepium (Jacq.) Kunth ex Walp., Erythrina americana Mill., E. fusca Lour., Diphysa robinioides Benth, Colubrina arborescens (Mill.) Sarg., Cordia alliodora (Ruiz & Pav.) Oken, Spondias bombin L., S. Purpurea L., Carica spp. Citrus spp., Manilkara zapota (L.) P. Royen, Pouteria sapota (Jacq.) H.E.Moore & Stearn, Diospyros digina Jacq., Theobroma bicolor Humb. & Bonpl., Chrysophyllum caimito L., Inga edulisMart., Artocarpus altilis (Parkinson) Fosberg, Pimenta dioica (L.) Merr., Bixa orellana L., Calathea lutea(Aubl.) E.Mey. ex Schult.

The cacao plantation studied was planted more than forty years ago with several varieties of cacao not specified. At present, the cacao plantation contains seven different varieties of cacao recognized by the producers and four clones introduced as a donation from the Mexican agriculture institute INIFAP. The cacao variation within the plantation ranges from the typical criollo variety with furrowed football shape fruits and white cotyledons (Theobroma cacao ssp. cacao) to the forastero type with smooth rounded fruits and purple cotyledons (Theobroma cacao ssp. sphaerocarpum) and intermediate forms in shape and color of cotyledons. We started this work as a result of seven years of interaction with Carmen Broca Martínez, the leader of the group, who has collaborated with us several times in Oaxaca State, as a trainer in grafting cacao plants, germination and caring of plants in the Mazatec lowlands (http://etnoecologia.uv.mx/diversidad_biocultural/mazateca/. The workgroup was contrary to that reported by Sagarpa (2105), where the average of cacao growers was around 63 years old. Here it is composed of eleven members between 16 and 26 years old and two adults are 53 and 64 years old. Anthropological interviews and informal meetings were conducted with the members of the group to organize and explain the necessity of reaching a different approach in the search for autonomy through self-sufficiency, solidarity and regional sustainability by applying diversified agroforestry systems. Important emphasis was put to explain and implement different strategies for the benefit of the group above personal interests, rewarding those who made bigger efforts and the sharing the surplus for the benefits of the group as described by Barkin and Lemus (2015).

The proof of concept

The proof of concept in this research consisted in designing a model, making it work, and showing the route of transformation from cacao seeds to high quality chocolate targeting a specific consumers market. It involved the selection of seeds, fermentation, drying, roasting and manufacture of high quality chocolate using European methods and techniques. Original designs and packaging were made along with internet marketing strategies (shop-online) in the attempt to reach informed consumers, willing to pay for a product according with conservation biology approaches where revenues will impact directly to small producers.

The proof of concept started during the cacao harvest season in December 2017, with the inventory of cacao plants in the plantation, classification and selection of the cacao varieties and clones. For the purpose of the experiment, one variety was selected and separated from the rest. The beans were fermented in special wood boxes, dried and roasted to obtain the cacao paste to be transformed into chocolate. In the laboratory, cocoa liquor was obtained where conching and tempering techniques were conducted for the manufacture of bars, bombons, truffles, and nutrition facts analyses were performed.

Materials

A minimum unit of production was designed in the laboratory for the manufacture of the cacao seeds into high quality chocolate using:

Roaster: A stainless steel device of around 2 kg of cocoa beans capacity at a fixed temperature of approximately 1350C. The beans are heated by convection heat (hot air inside the oven) and conduction hear (from the raster basket) resulting in a homogenous roasting of beans.

Cocoa cracker: stainless steel rollers with metal gears and a stainless steel hopper assembly.

Cocoa Melanger: A granite stone on granite stone grinder to grind cacao bean nibs to chocolate liquor. It is a machine to make chocolate covertures or bars. It has two black granite stone rollers that rotate at 135-140 rpm on a granite slab to reduce particles of sugar and cocoa to about 15 micron range. Grinds about 4.5 kg (8-10 lbs) of cocoa nibs.

Other tools used: Microwave oven; Refrigerator, a marble plaque 1 m x 60 cm and kitchen utensils such as spatulas, spoons, pots, etc.

The total investment in the design of the minimum unit of production cost around $3,000.00 U. S. Dls.

Results

In the study area, cacao beans are not manufactured or transformed into chocolate bars or its derivatives. The main form of cacao consumption in the area is as a drink, called “Pozol”, a pre-Hispanic popular drink made of a mixture of grind roasted cacao nibs, corn dough and water. Another popular drink called “polvillo” is made of a powder (grind roasted cacao and corn), sometimes added with cinnamon and allspice (Pimenta dioica (L.) Merril). Drinkable chocolate with milk or water, as it is usual in the highlands of Mexico and elsewhere is not common in this area of cacao production. In the attempt of reaching a different market to obtain better profits sometimes people grind roasted cacao seeds mixed with sugar, although this is not a common commercial activity. In general, chocolate bars are not a way of consuming cacao in the area of production of cacao. According with this research, there was no previous information in the workgroup regarding how to manufacture chocolate bars and its derivatives nor about the type of equipment needed to transform cacao beans beyond fermenting and drying the seeds.

The plantation

A census of the cacao trees planted in the two hectares study area was made to estimate the richness and abundance of each one of the varieties and clones of cacao in the plantation. According with the inventory, the two T. cacao subspecies are found in the plantation, from where producers distinguished a continuum of variation between these two extremes into seven varieties or forms:

1) Criollo, 2) Calabacillo, 3) Amelonado or Guayaquil, 4) Patastillo, 5) Aceitunado, 6) Broca Rosa, 7) Cundeamor. They also recognized four hybrids introduced: INIFAP 8, 1, 9 and 10. From around two thousand plants inventoried, Broca Rosa is the most abundant variety with (650 individuals), Amelonado or Guayaquil (560 individuals), Criollo (300 individuals), hybrids (400 individuals), around 140 individuals are composed by the rest of the varieties.

The variety Broca Rosa was used for the proof of concept due to its abundance in the plantation and resemblance to the criollo types (T. cacaossp. cacao). According with the leader of the group, Carmen Broca, this variety was brought to the plantation by some friends almost twenty years ago without certainty about its origin. It has been propagated since then due to a resemblance in morphology and flavor to the typical Criollo but with a better performance in the production of fruits per tree and resistance to diseases. Although the morphology of the fruit is similar to the Criollo type, the seeds are not white as the Criollo nor deep purple as the South American varieties but of a lighter color that producers call Rosa (no white-no deep purple), suggesting hybridization at some degree between Criollo and south American varieties.

Fermentation

Cacao fermentation is a succession of biochemical, microbial and enzymatic processes, necessary to obtain what is considered a high quality cacao. General characteristics of fermentation involve: a) The mucilage’s fermentation around the seed which promotes its degradation, production of acids and death of the embryo, avoiding its germination which impoverishes the quality of the bean. b) Unchain of biological-enzymatic reactions reducing bitterness and astringency, promoting the characteristic aroma, taste and color of chocolate (García-Alamilla et al. 2007).

Fermentation starts with the opening of the pods and storing the seeds in wood boxes fixed with holes to drain liquids. For the purpose of this project, we used boxes of 60 cm x 70 cm deep (to hold 160 kg of beans max.). In general, fresh seeds contain high contents of citric acid, glucose and fructose, that under low levels of oxygen, in a lapse of 12 hours promotes the development of yeasts which in turn degrade glucose and fructose into ethanol, acetic acid, oxalic acid, phosphoric acid, succinic acid and malic acid. Other compounds are produced such as isopropilic acetate, etil acetate, methanol, 1-propanol, 2,3 butanodiol, dietil succinate, 2-fenilethanol (García-Alamilla et al. 2007). During day one of fermentation, temperature raises to about 350 C, yeasts degrade citric acid, glucose and fructose and Ph raises as well. The increase of temperature and production of acetic acid are fundamental for a good fermentation to generate the production of aroma, taste and color of the bean. However, in this region, the fermentation of cacao most of the time does not fulfill the required standards for a high quality fermented bean due to the heterogeneity of cacao varieties within the plantations of each small producer. Different varieties of cacao produce seeds with different amounts of compounds (for example, citric acid, glucose and fructose among others) that accelerate or delay the development of microorganisms and enzymatic reactions. When seeds are harvested altogether, mixed and fermented without being classified, obviously a homogenous process of fermentation is difficult to achieve.

In this regard, it is important to point out that T. cacao, as a species, shows a continuum of variation and selection conducted by different cultures along a wide geographical distribution from South America to Southern Mexico (Ogata 2007). In this sense, it is well known that one extreme of the variation (T. cacao ssp. cacao), that is the typical Criollo, takes 3-4 days for an optimal fermentation while the other extreme of the variation (T. cacao ssp. sphaerocarpum), the typical calabacillo, requires 6-7 days. Therefore, the more homogenous the batch of beans to be fermented the better the final product. In this work, only seeds from Broca Rosa were selected and fermented in special wood boxes separated from others. The fermentation was conducted during a 6 day period, removing the beans in the box every 24 hrs to control the temperature as describe by García-Alamilla et al. (2007). Seeds were dried by sun, packed into henequen sacks and shipped to the laboratory in the facilities of Universidad Veracruzana in Xalapa, Veracruz.

Manufacture of Chocolate

The transformation of cacao beans into different forms of chocolate (bars, truffles, bonbons, etc.) was developed in Europe at least since the beginnings of the XIX century, far, very far away from where cacao plants naturally grow (Coe and Coe 1996). The methods and techniques involved in the manufacture as we know it today, are the result of the development of technology to manipulate the cacao contents and the blending with the diversity of products (spices, nuts, citrics, milk…) from all over the world, available in Europe. Weather conditions also played an important role to transform the different expressions of cacao contents into different products.

In general, manufacturing high quality chocolate involves three basic steps after the fermentation and drying of beans has been achieved: roasting, conching and tempering.

Several trails were done until reaching the desired conditions for manufacturing high quality chocolate with this variety. Once the parameters were controlled, two members of the workgroup were brought to the laboratory and trained in the manufacture of chocolate bars, bonbons and truffles. The trails initiated with the roasting of beans: An appropriate roasting is as important as the previous processes of the cacao chain production in order to obtain a high quality chocolate. However, “appropriate” is a relative term, which depends of the inherent characteristics of the beans such as variety, size, humidity, fermentation, among others. During a month period different roastings conditions were evaluated separating the beans by size, loads and exposition to different timings of temperature according with the equipment available in our laboratory. As described before, our roaster is a cylinder for 2 kg loads that reach a maximum temperature of around 135oC. As a result, our “appropriate” roasting was: a two kg beans load, exposed 1.5 hrs at 135oC. Roasted seeds were opened with the cocoa cracker and ground with a manual grinder to obtain the paste or liquor. The paste was conched in batches of 3 kg in the cocoa melanger, mixed with sugar at a proportion of 70% cocoa paste and 30% sugar for a 48 hrs period. The amount of cacao content was established with the purpose of highlighting the quality of flavor of the beans.

Tempering

After 48 hrs conching, the mixture cacao-sugar reaches a temperature of around 50oC and turns liquid. Cacao butter, an important component of the cacao paste, contains six different crystals with different melting points, shapes, and stabilities. When the mixture re-solidifies, temperature determines which crystals will be expressed in the solid state to confer an attractive appearance (consistence, bright and a melting point near body temperature).

The different crystals, melting temperature and expression are described in table 1 (Wikipedia 2018).

| Shape | Melting temperature | Notes |

| I | 17 °C (63°F) | Soft, crumbly, melts too easily |

| II | 21 °C (70°F) | Soft, crumbly, melts too easily |

| III | 26 °C (78°F) | Firm, poor snap, melts too easily |

| IV | 28 °C (82°F) | Firm, poor snap, melts too easily |

| V | 34 °C (94°F) | Glossy, firm, best snap, melts near body temperature (37°C) |

| VI | 36 °C (97°F) | Hard, takes weeks to form |

Chocolate bars

The confection of chocolate bars initiates with tempering. The liquid conched chocolate is poured and spread over a marble table to homogenize the crystals, let the temperature to low at 280C, then increased up to 340C and finally poured into the molds to let the crystal V to be expressed so that the solidified bars will show a glossy, firm shape, best snap and melting point near body temperature. Bars of around 80 grams were made in molds of 16.5 cm x 7.5 cm y .5 cm deep.

Manufacture of Bonbons and truffles

The manufacture of bonbons involves different techniques using 48 hrs conched chocolate mix to prepare bonbon forms and the making of fillings (ganaches) using fruits available such as: mango-habanero, coffee and wild blackberries.

Truffles were made following protocols proposed by Chef Edgar García Rico, based on European techniques.

Special boxes were designed for bonbons and truffles based on the designs previously used for the chocolate bars.

Aluminum wrapping

Bars were wrapped in 150 mm aluminum sheets (golden external-aluminum internal colors). Aluminum sheets follow United States FDA requirements/section 21CFR,177.1640.

Design

An image brand design was made especially for this project that included: a logo, an artwork to wrap the bars and an outer wrapper with information about the project and nutrition facts.

Nutrition Facts

Nutrition Facts label is required by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) of the United States as well as the Mexican Secretary of Economy on packaged foods and beverages. The Nutrition Facts label provides detailed information about a food’s nutrient content, such as the amount of fat, sugar, sodium and fiber it has (www.wikipedia.org). Since 1994 the Mexican government required a similar standard NOM/051/SCFI/1994 named as “Información nutrimental” developed by the Mexican Secretary of Commerce. Nutrition facts analyses were conducted to be included in the wrappers of the chocolate bars to fill the requirements of the Mexican Secretary of Commerce.

The nutrition facts results are as follows:

| Nutrition facts | |

| Size of portion: 50 g | |

| Energy Content: 1243 KJ (297 Kcal) | |

| Energy Content of fats: 888 kJ (212 Kcal) | |

| Fats (Lipids) | 23.55 g |

| Saturated fats | 14.50 g |

| Poliinsaturated fats | 0.80 g |

| Moninsaturated fats | 7.95 g |

| Colesterol | 0.00 g |

| Carbohydrates | 17.53 g |

| Fiber | 0.81 g |

| Proteins | 3.00 g |

| Sodium | 15 mg |

| Front cover (iconography) | |

| This product provides: | |

| Saturated fats 131 Kcal (64%) | |

| Other fats 79 Kcal (21%) | |

| Total sugar 73 Kcal (22%) | |

| Sodium 15 mg (0.74%) | |

| Energy 297 Kcal | |

| % of daily nutrition | |

Marketing

A website was designed in WordPress to describe the objectives of the project, workgroup and set up an online-store using PayPal for purchases. The website is embedded in our main website: etnoecologia.uv.mx/diversidad_biocultural. The project´s website: etnoecologia.uv.mx/diversidad_biocultural/selva_americana. The website for shopping: etnoecologia.uv.mx/diversidad_biocultural/tienda.

With the intent to reach an informed market, with assistance of a professional actor (Gerardo Trejoluna), a video-clip was made and included in the website, to point out the importance of diversified agroforestry systems as a means of conservation biology, sustainable use of natural resources and mitigation of climate change. https://youtu.be/7lcTa6W6RwA. A section called “historias de cacaotal” was made to document the oral history of cacao farmers to point out traditional knowledge, cultivation practices, pride for being a cacao grower and the ways they care about nature: http://etnoecologia.uv.mx/diversidad_biocultural/Selva_Americana/historias-de-cacaotal/. A ten minute documentary was also made and presented at the IX Ethnobiology congress in Morelia, Michoacan to show the progress and results of the project: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ULMutFalUsg. With this information we expect to call people´s attention on the importance of supporting projects producing high quality products on a sustainable basis of use and management of tropical rain forests.

Discusion

The proof of concept presented in this paper shows that high quality chocolate is possible to make at small scales with small cacao producers with the potential to bring important revenues that otherwise would be practically impossible. To achieve a product with international standards of quality, requires an organizational framework where solidarity in the group should be the thread to weave diversified systems of production, with the goal of seeking self-sufficiency, generating economic surpluses to be shared in group (rewarding those who most contribute to the project) and to invest the rest in local solutions for the well being of the community and regional sustainability.

The diversity of cacao varieties occurring in Mesoamerica represents the result of hundreds of years of selection made by different cultures in different geographical areas (Ogata 2003; Ogata 2007). In pre-Hispanic times, when cacao was used as currency, the Totonac, (nowadays northern Veracruz and Puebla states), in order to pay tribute to the Mexica empire, selected an ecotype of cacao adapted to thrive under low temperatures and rainfalls at the very extreme of the latitudinal natural distribution of the species. This section of the cacao genome, selected several hundred years ago, currently is unable to grow in high rainfall and temperature areas such as Southern Veracruz or Tabasco. In this sense, the diversity of cacao found in Mesoamerica, brings an exceptional opportunity to promote the cultivation of specific varieties in determined geographic areas under traditional agroforestry systems, which along with strict methods of fermentation, dry, roast and confection, will be the basis to generate a limited production of high quality chocolates, as mention before, to reach an informed consumers market with the economic benefit for small cacao producers.

As part of this work, we have tested the Totonac variety of cacao for making chocolate and found that this ecotype, produces a delicate taste and aroma very easy to distinguish from other varieties. Similarly, we tested samples growing in the deep of the Lacandon tropical rain forests in Chiapas and sinkholes in the Yucatan Peninsula with similar results. According with our results, the different cacao populations selected by different cultures in different geographical locations throughout Mesoamerica, constitute a mosaic of flavors and aromas (as in the wine). Finally, this approach may be the key for small producers to find an alternative to economy for their livelyhoods, as well as a benefit for an informed consumer attracted to a high quality product produced out of a conservation biology strategy using traditional agroforestry systems as a way for sustainable use of tropical rain forests, mitigation of global warming and deforestation.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by “Programa Arboles Tropicales” at the Centro de Investigaciones Tropicales (CITRO), Universidad Veracruzana. Thanks to the group of work “Hermanos Broca” and Dr. Joseph Cahill for previous review of this manuscript.

References

Arvelo MA., Delgado T, Maroto S, Rivera J, Higuera I y Navarro A (2016) Estado actual sobre la producción y el comercio del cacao en América. Instituto Interamericano de Cooperación para la Agricultura (IICA). Centro de Investigación y Asistencia en Tecnología y Diseño del Estado de Jalisco A.C. (CIATEJ). San José, Costa Rica.

Barkin D, Lemus B. (2015) “Soluciones locales para la justicia ambiental”. In: Hogenboom, B, et al., Gobernanza Ambiental en América Latina: Conflictos, Proyectos y Posibilidades, Buenos Aires: CLACSO.

Boff L (2013) La sostenibilidad. Qué es y qué no es. Sal Terrae. Santander.

Coe S., Coe M. (1996) The True History of Chocolate. Ed. Thames and Hudson. US.

Cody Ch (1995) The chocolate companion. A connoisseur´connoisseurs guide to the world’s finest chocolates. Simon & Schuster, New York.

Esteva, Gustavo. 2014. “Commoning in the new society,” Community Development Journal, Vol. 49 (Suppl. 1):i144-i159.

García-Alamilla P, Salgado-Cervantes MA, Barel M, Berthomieu G, Rodríguez-Jimenes G C, García-Alvarado MA (2007). Moisture, acidity and temperature evolution during cacao drying. Journal of food engineering. 79:1159-1165.

Higonnet E, Bellantonio M, Hurowitz G (2017) Chocolate´s dark secret. How the Cocoa industry destroys national parks. <http://www.mightyearth.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/chocolates_dark_secret_english_web.pdf> Off, C. (2006). Bitter Chocolate. Investigating the dark of the world´s most seductive sweet. Vintage, Canada.

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (2018). http://www.inegi.org.mx

Ogata N (2003) Domestication and distribution of the Chocolate tree (T. cacao L.) in Mexico. In: Gómez-Pompa A, Allen M, Fedick S (Eds.). Lowland Maya Area: Three millenia at the human-wildland interface. Haworth Press. New York. pp 415-438

Ogata N (2007) Cacao. Biodiversitas 72:1-5. Comisión Nacional para el conocimiento y uso de la biodiveridad.

Ogata N (2017) Cacao as a system of productive diversification for the development of southeastern Mexico. In: Castillo G (Ed.) Cacao: the food of the gods. Fundación Herdez. pp 59-82

FAO (2014) Agricultura familiar en América Latina y el Caribe. Recomendaciones de Política. Santiago, Chile. 473 pp.

Ruf FO (2012) The Myth of Complex Cocoa Agroforests: The Case of Ghana. Hum Ecol Interdiscip J. 39(3): 373–388.

Sagarpa (2015) Estudio para mejorar la competitividad de los productores de cacao en localidades de alta marginación en el Estado de Tabasco. Resumen ejecutivo. Sagarpa-Universidad Autónoma de Zacatecas “Francisco García Salinas”.

Sagarpa (2017) Cacao Mexicano: Planeación agrícola nacional 2017-2030. https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/256425/B_sico-Cacao.pdf

Toledo VM, Barrera-Basols N (2008) La memoria biocultural. Perspectivas agroecológicas. Icaria editorial. Barcelona.

Waldron A, Justicia R, Smith L, Sánchez M (2012) Conservation through Chocolate: a win-win for biodiversity and farmers in Ecuador’s lowland tropics. Conservation Letters 5 (2012): 213–221.

Wikipedia (2018) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chocolate#Tempering. www.wikipedia.org.